This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist’s weekly newsletter here.

To construct all the solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicle batteries, and other technologies needed to combat climate change, we're going to require a significantly higher quantity of metals. a lot more metals. Extracting these metals from the Earth causes harm and pollution that put ecosystems and communities at risk. However, there's another possible source of the copper, nickel, aluminum, and rare-earth minerals needed to address climate change: the mountain of electronic waste humanity discards each year.

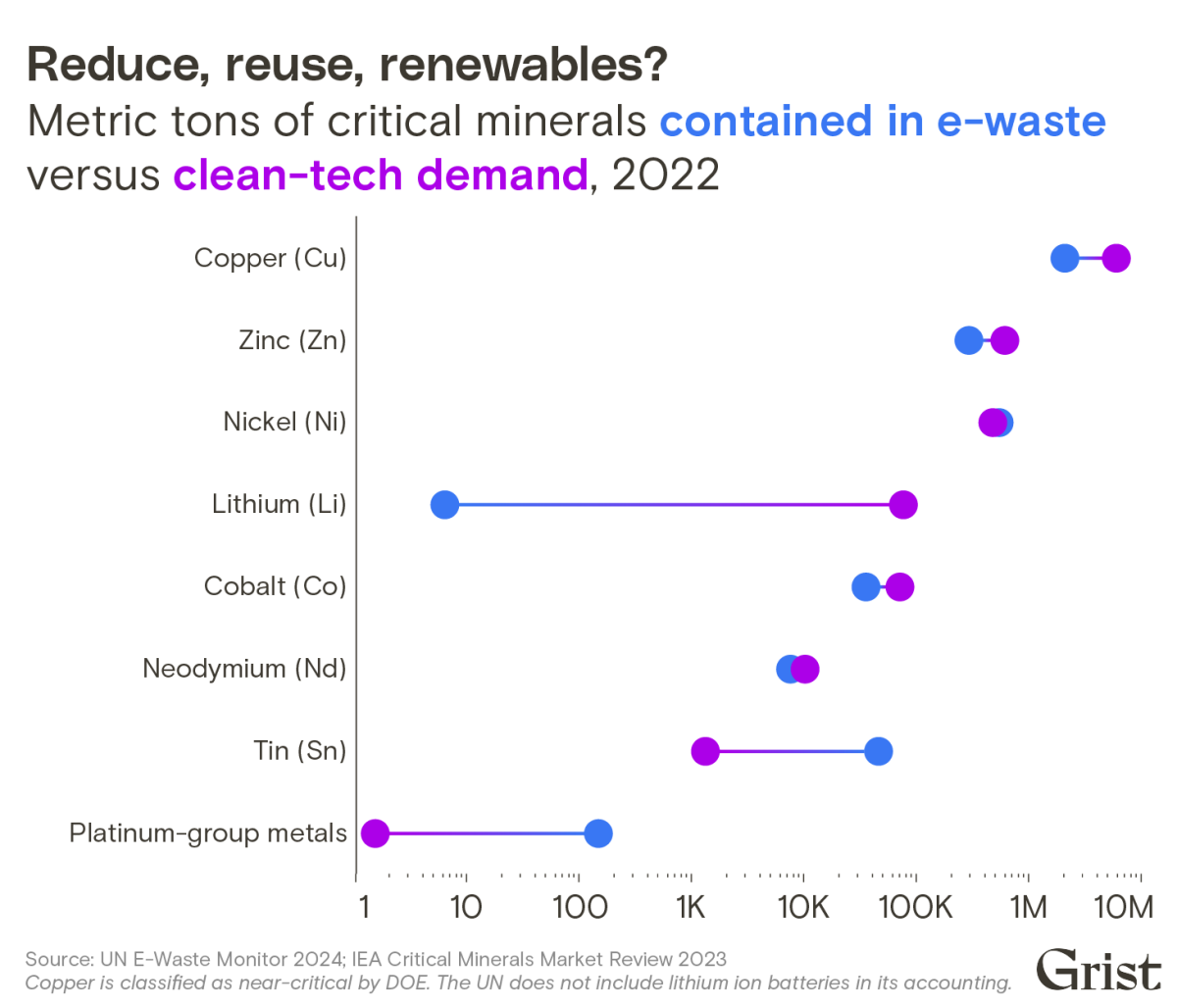

Precisely how much of each clean energy metal is contained in the laptops, printers, and smart fridges discarded by the world? Until recently, this was largely unknown. Data on less well-known metals like neodymium and palladium, which are crucial in green energy technologies, has been particularly difficult to obtain.

Now, the United Nations has made an initial effort to fill in these data gaps with its latest report on e-waste around the world. Released last month, the new Global E-Waste Monitor reveals the astonishing scale of the e-waste crisis, which reached a new peak in 2022 when the world disposed of 62 million metric tons of electronics. And for the first time, the report provides a detailed breakdown of the metals present in our electronic garbage, and how often they are being recycled.

“There is very little reporting on the recovery of metals [from e-waste] globally,” lead report author Kees Baldé told Grist. “We felt it was our duty to get more facts on the table.”

One of those facts is that some staggering quantities of energy transition metals are ending up in the trash.

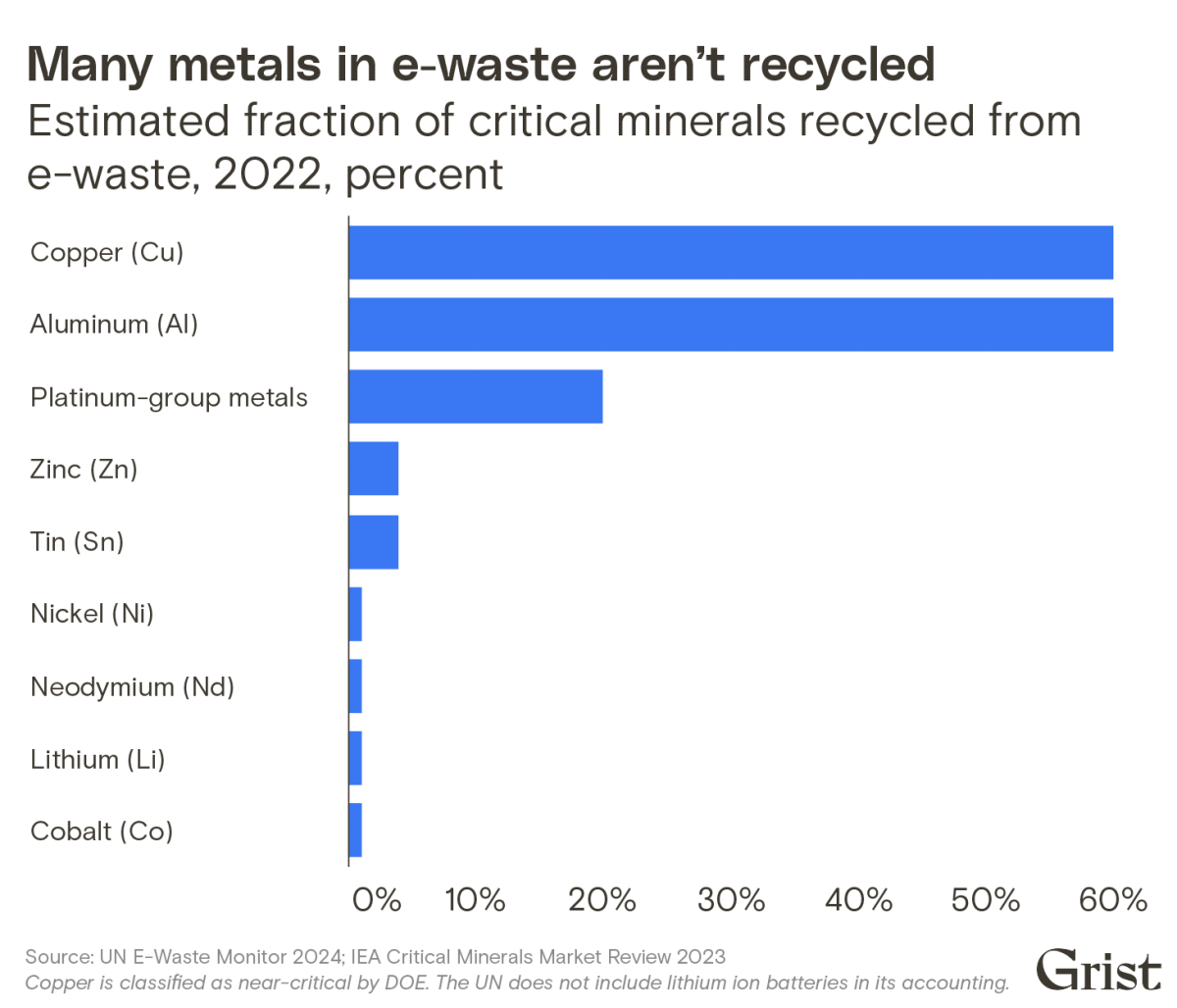

Two of the most recyclable metals found abundantly in e-waste are aluminum and copper. Both are expected to play crucial roles in the energy transition: Copper wiring is widespread in a variety of low- and zero-carbon technologies, from wind turbines to the power transmission lines that carry renewable energy. Aluminum is also used in some power lines, and as a lightweight structural support metal in electric vehicles, solar panels, and more. Yet only 60 percent of the estimated 4 million metric tons of aluminum and 2 million metric tons of copper present in e-waste in 2022 got recycled. Millions of tons more wound up in waste dumps around the world.

The world could have used those discarded metals. In 2022, the climate tech sector’s copper demand stood at nearly 6 million metric tons, according to the International Energy Agency, or IEA. In a scenario where the world aggressively reduces emissions in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, copper demand for low-carbon technologies could nearly triple by 2030.

Aluminum demand, meanwhile, is expected to grow up to 80 percent by 2050 due to the pressures of the energy transition. With virgin aluminum production creating over 10 times more carbon emissions than aluminum recycling on average, increased recycling is a key strategy for reducing aluminum’s carbon footprint as demand for the metal rises.

For other metals used to transition to different energy sources, the rates of recycling are much lower. An example is the rare-earth element neodymium, which is used in the permanent magnets present in various tools and devices, such as iPhone speakers, electric vehicle motors, and offshore wind turbine generators. wind turbine generators. In 2022, Baldé and his colleagues estimated that there were 7,248 metric tons of neodymium in e-waste around the world. This amount is roughly three-quarters of the 9,768 metric tons required by the wind and EV sectors that year, according to the IEA. However, less than 1 percent of all rare earths in e-waste are recycled due to the underdeveloped recycling technologies and the challenges and costs associated with collecting rare earth-rich components from technology. immaturity of the underlying recycling technologies, as well as the cost and logistical challenges of collecting rare earth-rich components from technology.

Baldé said that the process of collecting and separating rare-earth magnets for recycling is quite troublesome, despite the fast-growing rare-earth needs of the EV and wind energy sectors. He also mentioned that there is no incentive from the market or legislators to recover them. fast-growing rare-earth needs, “there is no push from the market or legislators to recover them.”

The metals found in e-waste may not be useful for every climate tech application, even after recycling. For example, nickel is heavily used in the lithium-ion batteries of electric vehicles, with over 300,000 metric tons being consumed in 2022. The demand for nickel in EVs could increase tenfold by 2050, as per the IEA. However, although the world’s e-waste contained more than half a million metric tons of nickel in 2022, most of it was within alloys like stainless steel. Instead of being separated, this nickel gets recycled into other steel products, as explained by Kwasi Ampofo, the lead metals and mining analyst at energy consultancy BloombergNEF. While some of this recycled steel may end up in wind turbines and other zero-emissions technologies, it does not directly contribute to meeting the much larger nickel demands of the EV battery market. could wind up in wind turbines and other zero-emissions technologies. But it won’t directly help to fill the much larger nickel demands of the EV battery market.

In some cases, e-waste may represent a significant source of specialized energy transition metals. Despite their small quantity, certain platinum group metals found on printed circuit boards and inside medical equipment are already being recycled at high rates due to their value. According to Jeremy Mehta, technology manager at the Department of Energy’s Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies Office, recycling palladium from e-waste could help meet the growing demand for these metals in fuel cell technologies and clean hydrogen production, supporting the transition to clean energy. palladiumRecycling palladium from e-waste could help meet the growing demand for these metals in fuel cell technologies and clean hydrogen production, supporting the transition to clean energy,” Mehta said.

For the energy transition to fully utilize the metals present in e-waste, improved recycling policies are necessary. This could involve policies that mandate product manufacturers to design their products with disassembly and recycling in mind. Josh Blaisdell, who oversees the Minnesota-based metals recycling company Enviro-Chem Inc., mentioned that when a metal like copper isn’t being recycled, it's often because it's in a smartphone or another small consumer device that isn't easy to dismantle. Enviro-Chem Inc., highlighted the need for design-for-recycling standards, Baldé proposes the implementation of metal recovery requirements to motivate recyclers to recover some of the non-precious metals present in small quantities in e-waste, such as neodymium.

In March, the European Council approved a new rule that sets a goal by 2030, 25 percent of “critical raw materials,” like rare-earth minerals, used in the European Union will come from recycled sources. This is not a mandatory goal, but Baldé says it could push for laws that require metal recovery.

Getting more of the metals from e-waste will be difficult, but there are many reasons to do so, Mehta told Grist. That’s why, last month, the Department of Energy, or DOE, started a prize for e-waste recycling that will give up to $4 million to competitors with ideas that could “substantially increase the production and use of critical materials recovered from electronic scrap.”

“We need to increase our domestic supply of critical materials to fight climate change, respond to emerging challenges and opportunities, and strengthen our energy independence,” Mehta of the DOE said. “Recycling e-scrap domestically is a big opportunity to reduce our reliance on hard-to-source new materials in a way that is less energy intensive, more cost effective, and more secure.”

This article first appeared in Grist at https://grist.org/energy/staggering-quantities-of-energy-transition-metals-are-winding-up-in-the-garbage-bin/.