This article was first published on Knowable Magazine.

In the dry desert of Nevada, there is a unique power plant that uses heat from the Earth to generate energy, rather than relying on the sun or wind.

This plant, called Project Red, brings water deep underground, where the rocks are hot enough to heat it. Then, the heated water is brought back up to power generators. Since last November, this clean and Earth-powered energy has been added to the local grid in Nevada.

Geothermal energy, which is constantly emanating from the Earth's hot core, has been mainly used in specific volcanic areas like Iceland. However, energy enthusiasts have envisioned using Earth power in places without such geological conditions, like the Nevada site of Project Red, developed by energy startup Fervo Energy.

Advanced geothermal systems have been in development for many years, but they have been expensive and technologically challenging. They have also caused earthquakes. However, experts are optimistic that newer projects like Project Red could mark a turning point by using techniques from oil and gas extraction to improve reliability and cost-efficiency.

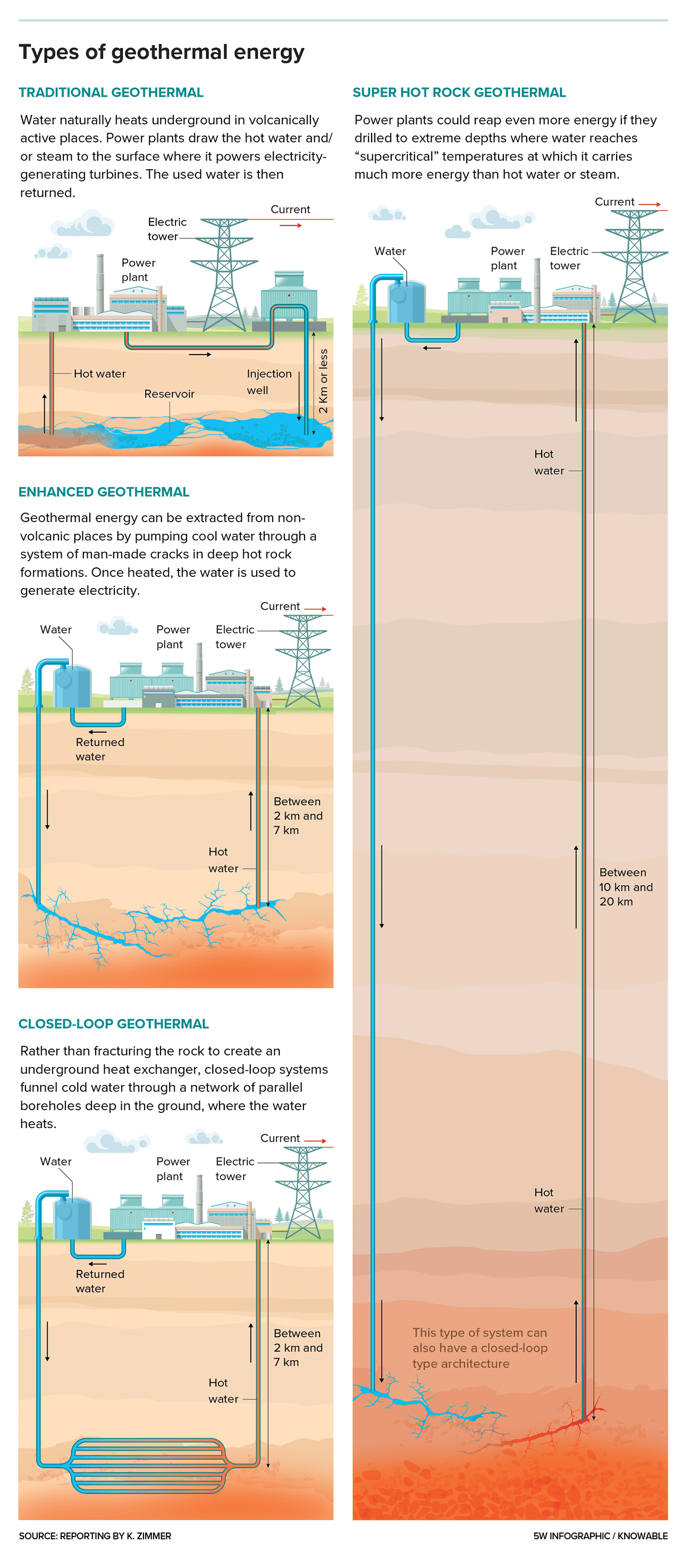

These advancements have raised hopes that with sufficient time and investment, geothermal energy, which currently only produces less than 1 percent of the world's electricity and 0.4 percent in the United States, could become a mainstream energy source. Some believe that geothermal could help transition the energy system away from fossil fuels by providing continuous backup to intermittent energy sources. Experts hope that with the transition to a carbon-free grid, geothermal energy becomes essential. Currently, it only accounts for less than 1 percent of the world's electricity and 0.4 percent in the United States., and Geothermal energy engineer Roland Horne from Stanford University is optimistic about its potential: “It’s been, to me, the most promising energy source for a long time. But now that we’re moving towards a carbon-free grid, geothermal is very important.”Geothermal energy works best where there is heat and permeable rock to carry water. In places where there is molten rock near the surface, water will move through porous volcanic rock, warm up, and rise as hot water or steam. solar and windThis energy source relies on water or steam that is at least around 300 degrees Fahrenheit to generate electricity. Kenya generates nearly 50 percent of its electricity through geothermal energy, while Iceland, New Zealand, and California also rely on it for a significant portion of their electricity needs. There are untapped geothermal resources in the western United States, according to geologist Ann Robertson-Tait, president of GeothermEx, a geothermal energy consulting division at the oilfield services company SLB. However, the natural, high-quality geothermal resources are running out, encouraging experts to explore ways of extracting geothermal energy from more difficult-to-reach areas. Getting that heat requires drilling deep and creating cracks in non-volcanic, dense rocks to let water flow through. Since 1970, engineers have been working on “enhanced geothermal systems” (EGS) to do just that.

engineers have been developing “enhanced geothermal systems” (EGS)

similar to the fracking used for extracting oil and gas, EGS apply high-pressure water to create cracks in deep rocks. These cracks and water form an underground radiator where water heats before rising to the surface through a second well. Many EGS installations have been built in the United States, Europe, Australia, and Japan, mostly as experimental and government-funded projects with varied success.

A well-known EGS plant in South Korea was suddenly closed in 2017 due to likely causing a 5.5 magnitude earthquake

; any type of fracking can add pressure to nearby tectonic faults. Other problems were technical—some plants didn’t create enough fractures for efficient heat exchange, or fractures traveled in the wrong direction and failed to connect the two wells. However, certain efforts became successful power plants, including several German and French systems built between 1987 and 2012 in the Rhine Valley where existing fractures in the rock were utilized.But overall, there hasn’t been enough interest to develop EGS into a more reliable and profitable technology, according to geophysicist Dimitra Teza of the energy research institute Fraunhofer IEG in Karlsruhe, Germany, who assisted in developing some of the Rhine Valley EGS systems.

Geothermal electricity has traditionally been limited to volcanic regions where underground heat is readily accessible. However, new types of power plants are making it possible to harness geothermal heat elsewhere in the world. Credit: Knowable Magazine New momentum

There are solutions for both safety and technological problems. Strong protocols exist for preventing earthquakes, such as by avoiding drilling near active faults. Long-term monitoring of operating EGS plants in France and Germany has only recorded minor tremors, increasing confidence in the safety of the technology. Moreover, drilling and fracking techniques have significantly improved due to the shale industry boom in oil and gas extraction since the 2010s. “Since then, we’ve seen a renewed interest in EGS as a concept, because the techniques that are central to EGS were perfected and brought down significantly in cost during that time,” says Wilson Ricks, an energy systems researcher at Princeton University. For example, in 2015, the US Department of Energy started a research site in Utah specifically to advance EGS technologies. Several new North American startups, including Sage Geosystems and E2E Energy Solutions, are developing new EGS systems in Texas and Canada, respectively. The most advanced is Fervo Energy, which has applied several techniques from the shale industry at its Nevada plant, now supplying a local grid that includes energy-consuming data storage centers owned by Google. (Google partnered with Fervo to develop the plant.)

Engineers drilled nearly 8,000 feet downward into the Nevada rock, reaching temperatures of almost 380 degrees Fahrenheit. At the bottom, they drilled another 3,250-foot horizontal well to expand the area of hot rock that the system touches, similar to the technique used in oil and gas extraction to maximize yield. The company also fractured the surrounding rock at several sites along the horizontal well to create a broader web of cracks for water to trickle through. Technologically speaking, compared to earlier EGS efforts, “they are, in fact, a big step forward,” says Horne, who is on Fervo’s scientific advisory board.

It's unclear how these new EGS systems will perform in the long term. One advantage of systems like Fervo’s is that they can be made more profitable by taking advantage of energy price fluctuations. According to recent research by Ricks, a Princeton colleague, and several experts at Fervo Energy, EGS systems can be made more profitable by taking advantage of energy price fluctuations. Operators could plug the exit wells, causing water to accumulate inside the system, building up pressure and heat. Then the energy could be extracted during times when it is most valuable, such as during cloudy or windless periods when solar or wind aren’t working.

Ricks says that what the EGS field needs right now is the funding to build and test more systems to inspire investor confidence. “This all needs to be very well proven, out to the point where the perceived risk is low,” he says.

A turning point for geothermal? The US Department of Energy recently awarded $60 million in funding to three demonstration projects for EGS and related technologies as part of a broader initiative to speed up EGS development.To increase a few percent could help in a global energy transition aiming to get to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. “If in fifteen, twenty years, EGS is viable, I think it could play a huge part,” says Nils Angliviel de La Beaumelle, who recently coauthored an article on the global outlook for renewable energy in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources. awarded $60 million in fundingto three demonstration projects for EGS and related technologies as part of a

broader initiative to speed up EGS development . One 2019 report from the agency estimated that, with advances in EGS, geothermal power could represent around 60 gigawatts (60,000 megawatts) of installed capacity in the United States by 2050around 60 gigawatts (60,000 megawatts) of installed capacity in the United States by 2050 , generating 8.5 percent of the country’s electricity—a more-than-20-fold increase from today. and Even an increase of a few percent could aid in a global energy transition that’s aiming to get to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. “If in fifteen, twenty years, EGS is viable, I think it could play a huge part,” saysNils Angliviel de La Beaumelle

coauthored an article on the global outlook for renewable energy in the

Annual Review of Environment and Resources Other geothermal technologies may also help. Some companies are exploring the feasibility of “super hot rock” geothermalexploring the feasibility of “super hot rock” geothermal

In southern Germany, the energy company Eavor is constructing the first ever geothermal system that operates in a closed loop: After pipes direct water into the deep rock, the system spreads out into a network of parallel boreholes, with water never entering the rock. This is a more predictable, though less efficient, method of heating water, as it avoids uncertainties related to fracturing the rock correctly, according to Teza. She is enthusiastic about the investment in these technologies and believes it can only be beneficial.

In general, this is a crucial moment for geothermal energy, not only for producing carbon-free electricity, as noted by Robertson-Tait. Geothermal brines extracted from the Earth are

abundant in lithium and other essential minerals

that can be utilized in the production of environmentally friendly technologies such as solar panels and EV batteries. There is a growing trend to utilize direct geothermal heat for heating buildings, whether through shallow heat pumps for residential buildings or larger systems designed for entire districts, such as those already in place in Paris and Munich. Some oil and gas companies are showing increasing interest in developing various types of geothermal systems, recognizing the inevitable change, as mentioned by Robertson-Tait. She believes that since our Earth is geothermal, we should do everything possible to make use of it.This article was originally published in Knowable MagazineGeothermal energy, previously limited to regions with volcanic activity, is set to become a much more adaptable energy source due to new technologies.

Even an increase of a few percent could aid in a global energy transition that’s aiming to get to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. “If in fifteen, twenty years, EGS is viable, I think it could play a huge part,” says Nils Angliviel de La Beaumelle, who recently coauthored an article on the global outlook for renewable energy in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources.

Other geothermal technologies may also help. Some companies are exploring the feasibility of “super hot rock” geothermal—essentially, a young, extreme variant of EGS that involves drilling down even deeper into Earth’s crust, to a depth where water reaches a “supercritical” vapor-like state that allows it to carry much more energy than either steam or liquid. In southern Germany, the energy company Eavor is building the world’s first “closed-loop” geothermal system: Once pipes funnel water into the deep rock, the system fans out into a network of parallel boreholes, without water ever penetrating the rock. That’s a more predictable—albeit less efficient—way of warming water, as it doesn’t involve uncertainties around fracturing the rock in the right way, Teza says. “I’m really excited to see that there’s investment into these technologies,” she says. “I think it can only help.”

On the whole, it’s an important moment for geothermal energy—and not just for providing carbon-free electricity, Robertson-Tait says. Geothermal brines hauled out of the Earth are rich in lithium and other critical minerals that can be used to build green technologies like solar panels and EV batteries. There’s a growing push to use direct geothermal heat to warm buildings, either through shallow heat pumps for residential buildings or larger systems designed for entire districts—like Paris and Munich already have.

Some oil and gas companies, recognizing that a change is coming, are increasingly interested in building geothermal systems of various kinds, says Robertson-Tait. “Our Earth is geothermal,” she says, “and so I think we owe it to ourselves to do everything we can to use it.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine