Life may "find a way", but how living things change over time is not a neat and orderly process. Instead of a organized family tree with straight lines for each new generation, the birth of a new species is much more complicated in reality. New research into one butterfly genus found in the Amazon shows just how complicated those evolutionary lines may be. Hybrids mating between some species can create new butterfly species that are genetically different from both parent species and their ancestors. The findings are described in a study published April 17 in the journal Nature.

A third hybrid

In the study, the team focused on the brightly colored Heliconius group of butterflies found in Central and South America. They are a common model for studying how butterfly wing patterns evolved due to the wide variety of wings within the group. In an 1861 letter to Charles Darwin, naturalist Henry Walter Bates referred to the Heliconius butterflies found in the Amazon as “a glimpse into the laboratory where Nature manufactures her new species.”

For a deeper look into Heliconius’ evolution, the team on this new study utilized the power of whole-genome sequencing. All living organisms have DNA that is made of four nucleotide bases–adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. If you know the sequence of bases, you can identify the organism’s unique DNA fingerprint known as a pattern. Sequencing determines these patterns and whole genome sequencing in a lab can determine the orders of these bases in one process.

You might have more in common with the sea lamprey than you realize.]

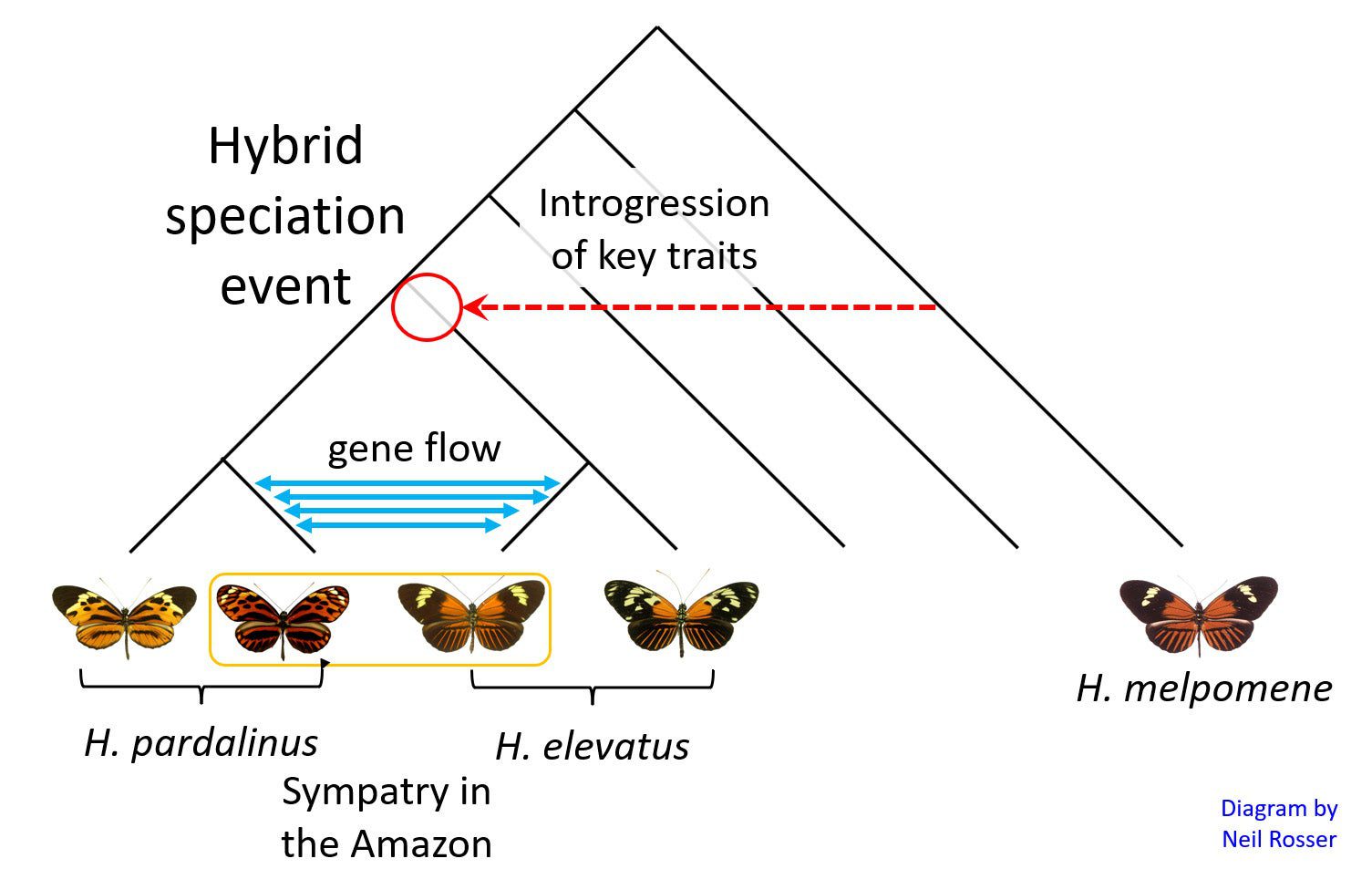

The whole-genome sequencing indicated that a mating event occurred about 180,000 years ago between Heliconius melpomene and the ancestor of today’s Heliconius pardalinus butterflies. This event produced a third hybrid species called Heliconius elevatus. Although it is descended from hybrids, H. elevatus is also a distinct butterfly species and has its own individual traits. These include color pattern, wing shape, flight characteristics, mating preferences, and more. All three of these distinct species now fly together across a wide area of Amazon and indicate more evidence that hybrids are not always sterile as sometimes previously thought.

“Historically, hybridization was thought of as a bad thing that was not particularly important when it came to evolution,” study co-author and Harvard University biologist Neil Rosser said in a statement. “But what genomic data have shown is that, actually, hybridization among species is widespread. Over the last 10 or 15 years, there’s been a paradigm shift in terms of the importance of hybridization and evolution.”

An evolutionary surprise

According to the team, this may alter how we view species and speciation. Scientists had generally believed that hybridization inhibited the generation of new species. Hybrid organisms are often born unhealthy or sterile and can’t reproduce, particularly when they are born with two different sex chromosomes. Most species are not perfectly intact tight units, but instead exchange a lot of DNA and can be considered “quite leaky.” The species that are evolving are actually exchanging genes constantly and it can trigger the evolution of new lineages.

“Usually, species are considered to be unable to produce reproductively fertile hybrids. This is according to study co-author and Harvard University biologist James Mallet. said in a statement.

This is not the case for Heliconius butterflies. They demonstrate that hybridization not only occurs, but also leads to the formation of a new species. Although there is now evidence of hybridization between species, it has been challenging to confirm its involvement in speciation.

Butterflies are capable of remembering specific flower foraging routes.]

“The question is: How can you merge two species and generate a third species from this merger?” said Mallet.

This new study offers scientists a way to further comprehend the processes of hybridization and speciation in evolution. It may also contribute to addressing the planet’s biodiversity crisis, as thoroughly understanding the concept of “species” at a genetic level is crucial for conservation. Additionally, it may aid in understanding the carriers of certain diseases. Various species of mosquitoes transmit malaria, and although they are closely related, we still do not know how they interact or produce new hybrids like Heliconius butterflies do.

Similar to the process of evolution, this area of research will continue to unravel as biologists gain further insights into what truly defines a species.