For nearly half a century, social scientists have operated under the assumption that all basic human emotions are universally recognizable. Countless cross-cultural experiments—not to mention a few television shows—have both directly and implicitly referenced the notion that every person on earth expresses facial emotion in the same way. Regardless of cultural context, we can all interpret happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust in the expressions of the people around us.

This belief has impacted countless studies and our general understanding of how emotions affect our daily lives, and it stemmed largely from the 1972 research of psychologist Paul Ekman. According to research published this month in the journal Emotion, however, it’s wrong.

Led by Northeastern University’s Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett and her post-doctoral researcher Maria Gendron, the new study shows that facial emotional recognition isn’t universal at all, and that previous studies pointing to universal expressions used methods that were highly dependent on context. In reality, a person’s ability to correctly register the emotion on another’s face hinges entirely on how those emotions are presented.

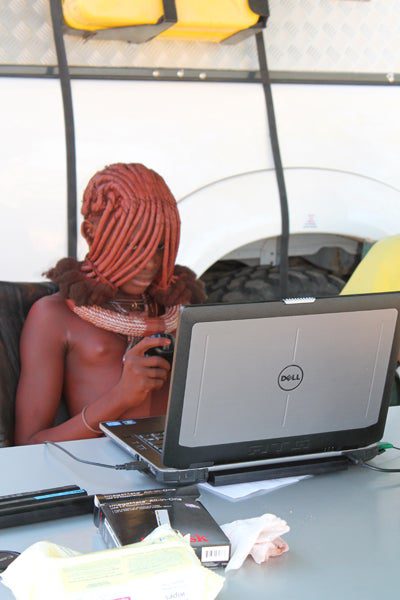

Skeptical both of the original research methods used to prove the “universality” theory, which involved prompting subjects with emotion words and asking them to label expressions with them, Barrett and Gendron led a team of researchers from Northeastern, the University of Essex, and the University of Namibia in conducting a cross-cultural experiment. Using Americans and members of the Himba ethnic group, a traditional northeast Namibian culture notable for its isolation from almost all Western cultural influence, the tram investigated whether recognition of facial expressions might instead be contextual, and whether subjects’ ability to correctly label expressions might hinge entirely on cues from the experimenters.

The Method

The way Barrett and Gendron went about proving their theory is disconcertingly simple. Researchers split two participant sets—a group of 68 Americans visiting Boston’s Museum of Science, and 54 Himba from two remote villages in Namibia—into two additional groups, a “free sorting” group and an “anchored sorting” group. (the latter meant to replicate the previously accepted Ekman studies, which were initially published in 1971 and required subjects from the Fore people of New Guinea to match a given set of words with corresponding photos).

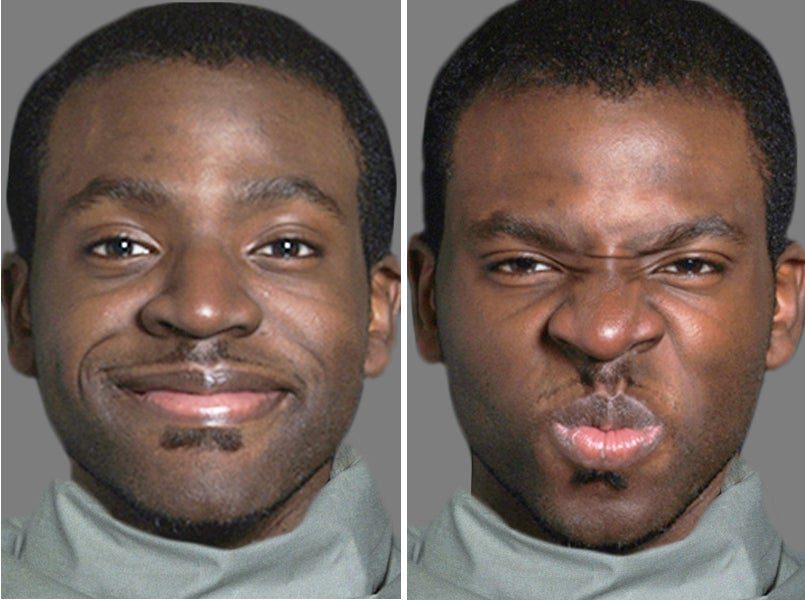

The researchers then showed subjects 36 photographs of three male and three female African Americans with their faces posed in the six different so-called “universal” emotional expression categories: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and neutral. In each set, the “anchored sorting” group was told those six emotion words and asked to sort the photos according to those categories, while the “free sorting” group was simply asked to sort the 36 photos into piles where each face in the pile is expressing the same emotion. There was no limit on the number of piles the “free sorting” group could create for their photos. Once they had sorted the photos, all participants were then asked to label each pile they had created.

The Results

The data set they produced in no way bolstered an argument for universality. While the anchored sorting groups performed in the way Ekman’s findings suggested they would—participants were able to sort according to the words provided to them with almost universal accuracy—the free-sorters were all over the map. Americans used “discrete emotion words” like “anger” and “disgust” to describe their piles, but also used “additional mental state words” like “surprise” and “concern.” Meanwhile, the Himba labeled their piles with physical action words, like “laughing” or “looking at something.” Free-sorters also did not sort into the six distinct piles that would support the universal recognition theory; instead, the piles varied in number. The only consistency across both groups seemed to be that participants sorted the faces well according to the positivity or negativity of the emotion and level of arousal (the extremity of the emotion).

“By giving people six words and six faces, you’re already pre-categorizing, you’re pre-loading the choices for the subject—you’re [actively] reducing ambiguity,” Barrett tells Popular Science. “You’re priming a set of emotion categories, providing a conceptual context for the subject, and that’s helping their response. So when we provide conceptual context, we get six piles. When we don’t, the subject gives you—they don’t give you a random sort, they certainly separate positive from negative, and they do better at separating some of the negatives from each other, but it’s not a perfect sort, by any means. It’s a very noisy sort.” In other words, those basic emotions aren’t really universally perceived at all—whether or not you’ve been culturally conditioned to look for them, and whether or not you’re given them as options in advance, absolutely matter. (For the record, though humans are pretty lousy at identifying each other’s expressions, robots do it really well these days.)

Almost Too Easy

There are literally thousands of experiments that claim emotions are universally perceived from the face.

In actuality, the evidence confirmed by Barrett and Gendron’s study has existed for decades. Universality champion Ekman himself conducted several studies around the same time he began getting attention in the late 1960s that used free sorting methods and found little evidence for universality, but those studies, unlike the ones that did find a cross-cultural correlation, were disregarded by peer-reviewed psychology journals of the era. Studies in the years since Ekman’s initial experiments have failed to find the correlation to support universality as well; Barrett and Gendron—who also conducted a complementary study, published earlier this year in Psychological Science, that found the same contextual pattern in the way we recognize basic emotion in each other’s vocalizations—are simply the first to concretely prove that context matters.

Still, this hasn’t seemed to matter for the countless ways in which the universality argument has been taken for granted in scientific, educational, pop-cultural, and even policy-making contexts. As Barrett and Gendron write, “This view is standard curriculum in introductory psychology, is used by government agencies to train security agents…and is a popular example when social science is communicated to the public (e.g., stories in National Geographic, Radiolab, etc.).” There are literally “thousands of experiments that casually claim that emotions are universally perceived from the face.” It would be impossible to measure the lasting effects of those offhand claims on the scientific and public understanding of emotion, but as more studies like Barrett and Gendron’s begin to emerge, it may be easier to poke holes in the establishments bolstered by those assumptions.

The ease with which this new study was able to invalidate the commonly referenced research about emotion recognition, in addition to the little-acknowledged research that preceded their study, points to chronic concerns about scientific research and how it’s shared. Not only does the acceptance that all people feel the same “basic” emotions in the same way and can detect those emotions in others’ faces and voices reflect the deeply rooted, mostly unintentional bias inherent in the research models of Western science (the “six basic inherent universal emotions” just so happen to be identified by American scientists, in English, for example); more basically, it reflects the public’s preference for accepting essentialist scientific ideas.

“People have a deeply held belief that anger, sadness, fear and so on are biologically basic, that they’re naturally occurring, immutable categories, and scientists just haven’t looked hard enough for the right brain circuit for each emotion yet,” says Barrett, “instead of [considering] the idea that every instance of anger or sadness or fear has a biological basis, but there isn’t a one-to- one correspondence between a facial expression and an emotion category. I think [the idea that emotions are contextual] is just too complex for people. It’s not the story people are interested in.”

The Future of Emotion?

Barrett and Gendron’s study—as well as most of the work done at Barrett’s Interdisciplinary Affective Science Laboratory, which conducts ongoing research into the basis (or bases, as is more likely) of emotion —posits that the “six discrete emotion categories” idea is a cultural concept created by Westerners.

“We have to understand that an emotion, like anger, is not a physical thing, one physical form with a physical essence,” says Barrett. “It’s a conceptual category, a heterogeneous population of instances…You feel lots of different angers, and your body does different things in anger; you behave different ways in anger depending on context, and science has to stop treating variability in all these different angers as if it’s error, and start treating it as if it’s meaningful and important.

And textbooks have to stop saying that there are six universal emotions that are universally experienced and expressed all around the world, because it’s not really clear that that’s true.”